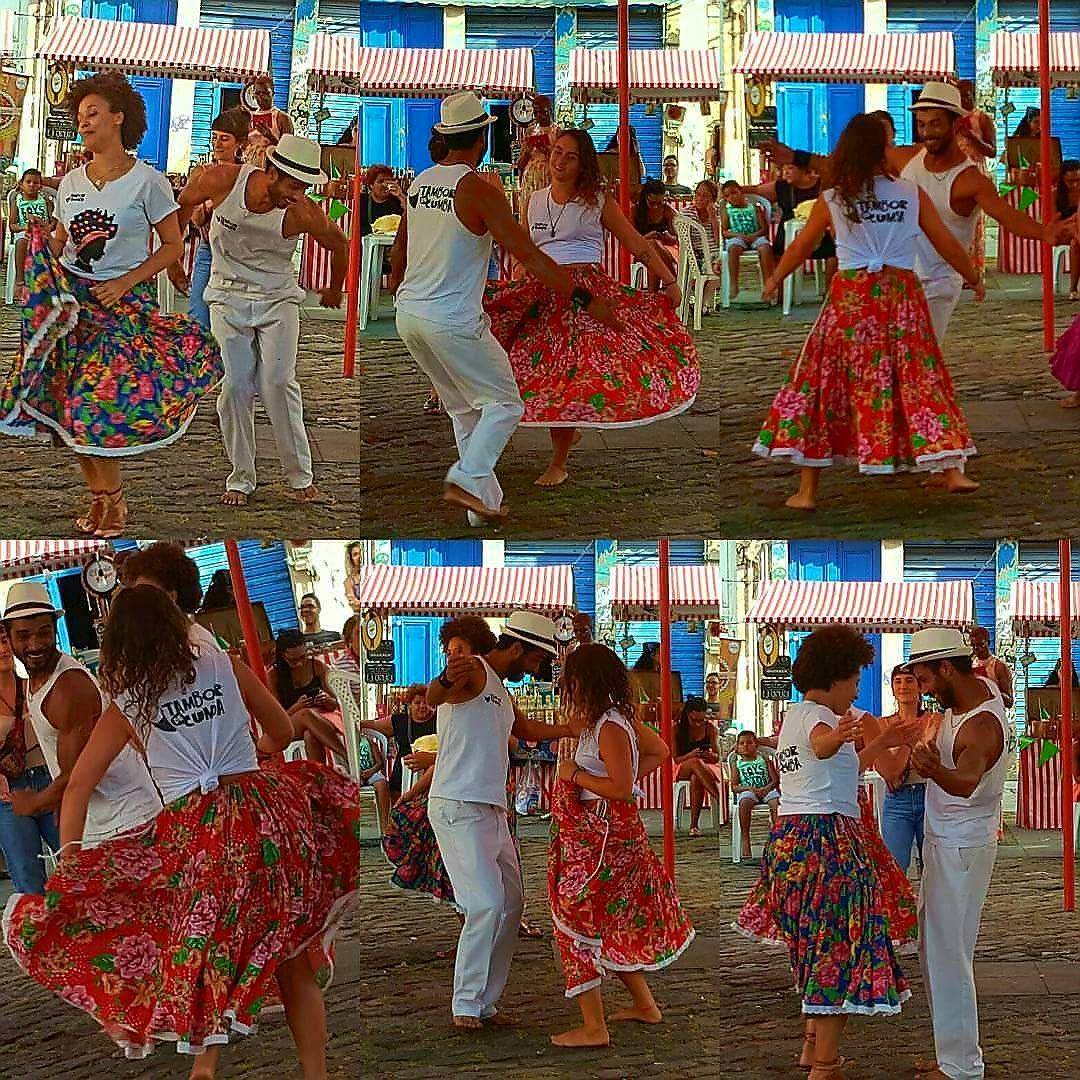

The estimates I found were not unanimous, falling far above and below a million enslaved Africans that had survived the voyages between continents over three centuries. They had been sold at what is today the excavated archaeological site in backdrop of the photo above, where I recently visited a capoeira and Afro-Brazilian dance group, Tambor de Cumba, in the area of the port of Rio de Janeiro called “Little Africa”.

Those stones reveal what is left of the infamous slave market, Cais do Valongo, which had been recently rediscovered during the port renovations that were part of the urban renewal of Rio de Janeiro for the Olympic Games. Even more recently, in 2017, the location was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I consider the heritage declarations the only good legacy of the Olympics for this city, as we awaken with a splitting hangover from a behind-the-scenes orgy that included a limitless budget for a few privileged guests and areas of the city, while the budget for the rest of its citizenry and the unglamorous places of the city seems to have vanished.

If numbers are actually capable of provoking emotion, it is staggering to imagine that Brazil had received some 4 million Africans, 40% of the slaves shipped to the Americas between teh 16th and the 19th centuries. But, like most people — I suspect — I don’t know what a million looks like, what it feels like, or what I should do with it. Even 388,000 — the number of Africans sent to the United States over the same period — is too big for me to imagine. But as I looked at the site of the Valongo Wharf, I realized that, although it was not the only slave market in Brazil, its handling of 60% of the slave traffic over the years would make the it the largest of its kind — at any time, anywhere.

But since, as humans, we are able to muster more empathy for individual suffering than for millions, much less for those on the other side of globe or distanced by centuries, I do not believe numbers are capable of provoking more emotion that words. That is why having read Homegoing by Ghanaian-American novelist Yaa Gyasi made the visit to Little Africa come alive, although the setting of her novel does not take place in Brazil. It might have been the fact that archaeologists encountered artifacts and amulets, when uncovering the site of the Valongo Wharf, which immediately immediately reminded me of how one particular amulet in the novel had travelled with a girl across continents and across time, from an Asante village on Africa’s Gold Coast during the colonization all the way to contemporary American high school. This young writer ambitiously strung the stories of a family across seven generations of two sisters like beads on the amulet, each accounting for the stories of an evil betrayal in a colonial African village, of a treacherous bondage and torture as a slave in an alien world, of the injustice of indenture, of a false-freedom in Harlem, New York, and of how prejudice manifests in America today. The sheer scope of the book makes it more than just the story of chattel slavery. Homegoing is a complete portrait of individuals, generations before and after the heinous crime against humanity, one that I had thought I had understood from history class.

I hadn’t.

Because such classes revealed only a sanitized history of distant facts and figures, devoid of the power of literature to turn history into a story that becomes a part of you, giving you personal experience, as if a witness— without which, my visit to a place like the Valongo Wharf might have been lost. Although not the only story of the African Holocaust to do so, Homegoing was the novel that touched me, teaching me not only how the wound that is chattel slavery had been inflicted, but how it has been left open, effecting people until today in ways I had not imagined.

Can you fathom the trauma of a teenage girl losing her family and surviving a voyage to wind up on the dock of an alien world? Quarantined upon arrival before being sold? As I stood at the Valongo Wharf, I imagined watching one of Gyasi’s protagonists witnessing any non-survivors of the voyage and quarantine being hurled into something like the adjacent Cemiterio dos Novos Pretos, the Cemetary of New Blacks, the site of the largest slave cemetery in the Americas. By then end of slavery, tens of thousands of bodies had been dumped and incinerated upon arrival in Rio de Janeiro. The violence of holocaust affected every generation that followed her, including those who are struggling to maintain the site, which today is the institute and museum by the same name, a cultural center dedicated to the memory of this holocaust, which had been inadvertently unearthed during a renovation of a house, only to encounter so many skeletons.

Gyasi’s saga is a marvel, having invented nothing less than many Anne Franks, through whose eyes many forms and effects of captivity can be seen. The novel reads a bit more like popular than literary fiction at times, something I attribute to her youth and having just cut short of biting off more than she could chew. But she pulled it off, writing a beautiful novel that I am sure will be compulsory for anyone wishing to comprehend what choices are made in freedom and in bondage, as well as the inseparable connection between Africa and America in the social struggles faced by society — and not only in the US. Homegoing could have taken place in Brazil or any of the other countries of the Americas that fostered a slave economy, regardless of the differences of culture and context.

“…The more he understood that sometimes staying free required unimaginable sacrifice.” — Yaa Gyasi, Homegoing

Unfortunately, the city of Rio de Janeiro is currently within nothing less than a political, financial, and social imbroglio in the aftermath of the Olympics, threatening the very preservation of Little Africa. Grassroots organizations are at the forefront of the fight to preserve this history, against those who might benefit from conveniently forgetting it. One such group is the Afro-Brazilian dance troupe, Tambor de Cumba, which is currently running a crowdfunding campaign to raise resources to support its first show “African Cosmogony: the world vision of the Yorubá people“. Any contribution will be greatly appreciated, and even rewarded with percussion and dance classes.

A final note: if you think slavery is a disturbing atrocity of the past, you’ve got some homework to do. It is so monstrously present all around us that it ought to keep us up at night. According to the Global Slavery Index, 45.8m were within the bondage that is called “modern slavery” in 167 countries in 2016 — a country you are probably comfortably sitting in right now.

One thought on “The Archaeology of Slavery & Book Review: “Homegoing” by Yaa Gyasi”