Gentrification in the Old New World

text and photos by Ricky Toledano

Ciudad Vieja refers to the Old Town that had lied within a fortress, the walls of which have long since been torn down to extend the streets from the port like a spider’s web. I was walking past the smiles of the locals towards the city’s starting point on the peninsula, almost to the end of Calle Sarandí, where, like most tourists, I could have turned right to go to Montevideo’s famous market, the Mercado del Puerto, but then I saw the glimmer of the waterfront in the cool autumn light of the city. Walking straight ahead to the Rio de la Plata, I passed abandoned buildings interspersed with bars and restaurants, both trendy and nostalgic, on a walk that led me through a Montevideo that is more aged than it is old.

I heard some different accents, including many from the newest wave of migrants from Cuba and Venezuela – as well as their wonderful music. Barbequing on the street in front of their homes in what seemed a crumbly yet vibrant neighborhood, the residents occupied the commons of the street intimately, laughing and shouting at one another. There were young boys walking dogs they did not clean up after. Old windows no longer reflected light. And on the lawn in front of the river that looks like an ocean was a group of Muslim men dressed in white, sitting cross-legged in a tight circle to recite the Koran. The walls of Old Town were littered with graffiti and many hauntingly beautiful street paintings. Surprisingly, and completely unlike my home in Rio de Janeiro, what I had perceived as a scenario of urban decay did not activate my spider sense for danger. Uruguay is an astoundingly safe place amid a very violent Latin America, and I was completely at ease to conduct my practice of observing the beauty of old buildings, their crafted doors and windows carved from a time when portals were given frames like paintings. I assessed the buildings for signs of the makeshift solutions of ageing, such as aluminum windows replacing original woodwork. I didn’t notice any, but I also could not pay too much attention upward, because the streets of older sections of Montevideo had been broadly mined by the residents’ dogs – which, like the absence of aluminum, could be a sign of something good or bad.

After an about-face from the Rambla Sur in Plaza Guruyú to re-enter the web, I was struck by an alarming red street painting. It read: “Don’t let gentrification catch you by surprise”. It also defined gentrification as “a process of transformation with the negative effects of increasing prices, expulsion of neighbors and loss of identity”.

That limited definition to an ambiguous problem incited reflection from an urban guy from Chicago, who has enough gray hair to have accompanied the process of urbanization in places as disparate as the US, Brazil, India and Mexico. I admit that I have always enjoyed the urban resuscitation of gentrification-as-progress: the way it revitalizes historic neighborhoods, makes them safer, improves infrastructure, and redirects urban sprawl with the creation of brownfield opportunities as opposed to greenfield. The issue of gentrification, however, requires much more than a spider sense. As expressed in red by the warning sign presenting gentrification-as-problem, inhabitants are endangered by displacement when neighborhoods become increasingly expensive, pushing out both immigrants and long-time residents, people who often go unrewarded for their efforts in maintaining a community.

I cannot help but imagine how prioritizing transportation over housing would hit (but not kill) two birds with one stone as the urban challenge of Chicago, the urban mess of Rio de Janeiro, or the urban chaos of Delhi would be tamed by distributing the possibilities of progress. A more immediate solution for endangered residents, however, might be a tax on the value of land, as opposed to the property inhabiting it. Such a measure would potentially return value to residents for their community efforts, and not to investors. It might also avoid the misuse of space, as in Montevideo, where abandoned and unoccupied property stand in protest.

My fascination with gentrification, however, lies in much more than the economic debate over cycles of development. The human cravings for security, comfort and pleasure are part of the search for a place to be happy – if indeed happiness is something that can be found in a place.

It cannot be. And one does not have to be a spiritual guru to know that. However, I do believe there are places more conducive to happiness than others, if only because beauty most certainly can be found in some places more than others. The public space is usually where the aesthetic experience can be shared – whether a hike up a mountain, a stroll in the park or down the avenue. Old buildings and streets become the object of gentrification for a reason. And that reason lies in the human search for beauty, which is hard to find behind gated enclaves and the soulless streets of contemporary, utilitarian architecture that is detached from a story, devoid of craftsmanship and decoration – to say nothing of community.

That is why people seek the beauty of the past and why it is so highly coveted. But was the past really more beautiful?

Apparently, pieces of it, yes, and it is also irreplicable. When I had visited abandoned havelis in remote villages of Rajasthan, India, I was impressed at how they had survived centuries of sandstorms and monsoons, but not pilfering. Much of the original woodwork, friezes and carvings had been swiped, probably worked into furniture and decorations to be found on high-rise balconies in Delhi, New York, or even in the Pocitos district of Montevideo, the upscale neighborhood I had found insipid while on my hike through the city. With immaculate and motionless streets of cement and glass, the vanilla of affluence often lacks taste.

Authentic was the missing flavor that came to mind when observing not only how beauty emerges out of the quality of materials, craftsmanship and artistry of the past, but also out of the ensemble of people who have maintained a story of the community they call home. Although I cannot imagine what development is going to look like two-hundred years in the future, I don’t see how the American pre-fab suburb or the towering cinderblock jungles of the developing world will become objects of gentrification the way Montevideo’s Palermo district, with its old homes on heavily tree-lined streets – adjacent to the Afro-Uruguayan cultural corridor of Isla de Flores and its local candombé music – are rapidly becoming another café and craft beer depot among the gentrified travel destinations of the world. Regardless, such a neighborhood is the kind of place that people want to be because it is connected to community, to tradition, to authenticity, to the past, and to beauty.

While I might have a taste for the art of the past, I have none of the longing for it that is nostalgia – an emotion I have called useless, and one that morphs into things dangerous when there is longing for partial-pasts or those that had never actually existed. Recent research has shown how people perceive the world immediately before they were born as a better place, one in which people were nicer and the world was safer. I would be interested in seeing how this research pans out across cultures, because I am not sure most Uruguayans find anything beautiful about at a recent past, one in which hundreds of citizens disappeared during the dictatorship that lasted from 1973 to 1985. In Montevideo, the March of Silence has been held in memory of the crime against the people every year since.

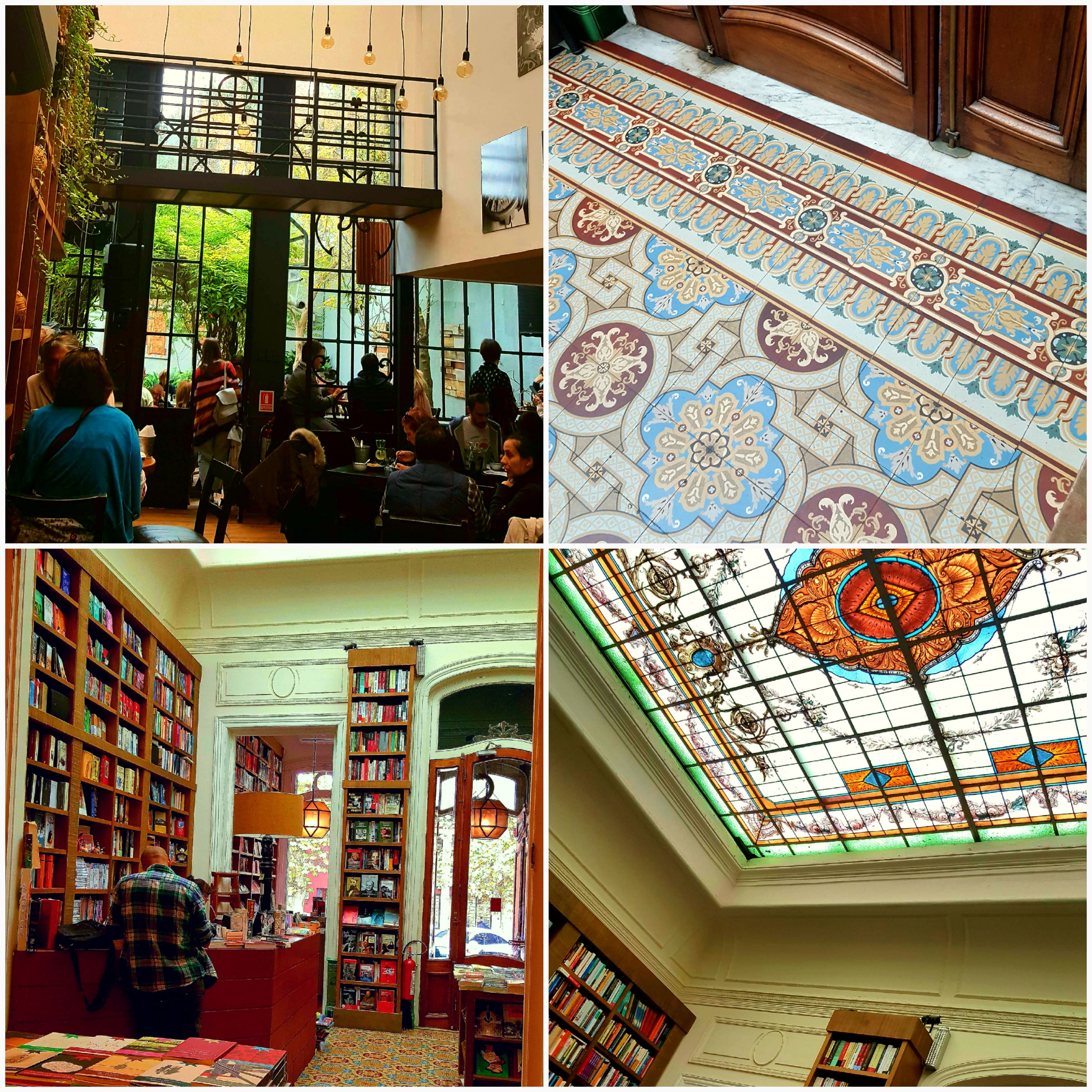

The past indeed contains ugliness like conquest, colonization, and dictatorship, which are edified as part of Montevideo and all the other cities of Latin America, maybe the world. Remember that Ciudad Vieja had not always been Old Town; there was a time it was new and built inside a fortress for a reason. Since it is unreasonable to expect times not to change, populations not to grow, cities not to transform, nostalgia is therefore a choice about when the past begins, the predilection of a story, as if there were no other, neither before nor after it. That choice provides a trap on both sides of the gentrification issue, one I avoid while walking the old streets of this world, meditating on the beauty that holds me in the present. This exercise has made me realize how much we need art: beholding beauty keeps us in the moment, suspended like a kiss – that instant when there is nothing missing – before the clouds of the past and the future return to obfuscate the present. Then the kiss ends, and the controversy begins, as I was reminded by the red sign announcing the local effort against the loss of neighborhood, character and affordability that is gentrification. There I was: yet another tourist spending a leisurely hour enjoying gentrification-as-progress, sipping specialty coffee in an expensively refurbished home-cum-bookstore in a historic and decayed district of Palermo.

Equally paradoxical was how infuriated I’d become while in that café, reading an article that [tried to] postulate logic for why it was perfectly humane to mourn the loss of a building over the loss the lives, because all grief is human – especially when uniting people under a globalized and tech-charged value for civilization and beauty, therein represented by Paris’s Cathedral of Notre Dame, which had gone up in flames. According to the article, not caring so much about the loss of thousands of lives in Mozambique after a recent cyclone had devastated the country – to say nothing of the plight of its survivors or any other of the many places of terror and destruction in this world – was to be considered understandable.

It isn’t. The argument was unconvincing. Its apology was stronger than its logic. The irony of the editorial was its delivering yet another example of the Eurocentric perspective it had proposed to refute by painting a picture of civilization that had become global.

Global civilization? I swallowed, Really?

That article was followed by the other distant tragedies – the ones that we care more about than those in our neighborhood – including the plight of orphan orangutans; the indigenous peoples of Brazil and their felled trees; the many refugees of Central America whose children are held captive; the whales starving to death because their bellies are filled with plastic; Yemen in the grip of war; and all the villages across this world that are running out of water. They were issues that warranted at least as much of the resounding outpour of emotion as Notre Dame. Yet, they did not.

Shocked to see the flames shooting up into the sky, I was initially patient as I saw the deluge of despair over Notre Dame. As an admirer of the architecture of times past, my reaction was also that of concern: such a loss of history and art is indeed immeasurable. But when I saw the beginning of what would only become a tidal wave of lamenting, I started tapping a finger on the table of that bookstore as I cocked an eyebrow and sucked my teeth. Although I was hardly the first to be suspicious of such global grief ladled over the fire of Notre Dame, I did not join the resounding contempt for the billionaires showering sums of money to restore the cathedral – and not Mozambique. How could I? At least those magnates had done something, while I had done nothing to help either cause. Besides, it was the collocation of resources emotional and not financial that I had found disturbing as I inspected people’s priorities – the act of a dictator who wants to decide how others should feel.

There is a little dictator inside of each one of us, I thought, musing on how all of us want to rule the world. That dictator swelled up on a recent trip to post-pandemic Mexico, where I encountered graffiti that blamed the swarms of gringos for the soaring prices of gentrification in Oaxaca and Mexico City. I found the resentment even in social media: there was a picture of the painting of “cactus fries” placed in the iconic McDonald’s cup, which I interpreted as gringos making “fast food” out of Mexico. In the caption, there was the comment that there were more gringos than students in the historic city of Guanajuato.

Were there, really? I thought, sensing the kind of conclusion that might be undercooked and dripping with bias. Checking numbers, I discovered that, indeed, tourism in Mexico had surged, second only to the ever-winning France for the world’s most visited country in 2023. Tourism represents some 8.5% of the GDP of Mexico, according to the OECD. That amount is so high that artists might be using creativity for more somber issues were that number to collapse under the trend placing the historic state among Mexico’s most violent. What is more, the dictator remained unconvinced that there are actually more tourists in Guanajuato than students, and if so, would that necessarily constitute a problem?

I’m sure it is for poor students, but I am also sure that it has been a boon for the city, a UNESCO world heritage site. I suspect the speed at which such change has occurred to be what itches most: post-pandemic inflation together with the siege of outsiders seeking happiness in more beautiful and comfortable cities than at home – earning dollars online while spending in pesos – has transformed places like Mexico City and Oaxaca with Airbnb housing crises. In other places around the globe, the upheaval has been acute for much longer. The citizens of Paris and Venice had already been dealing with the barbarians in their own cities for decades before the onslaught of digital nomadry, and they have since moved to regulate short-term rentals and even outdoor picnics.

When change is too much, too fast, perceptions get distorted even more than they may have already been misguided. Surveys have documented how residents systematically overestimate the number of foreigners in their midst. Change in one’s surroundings incites bias; it incites nostalgia and riles all the dictators to artless solutions for complex problems, solutions that are tailored to displease. Although there are people who have such a bad relationship with change that they complain about the weather, sudden snaps in temperature can indeed be uncomfortable. And gentrification in certain parts of Mexico has turned into the most scarlet of fevers.

At its most extreme is a case so severe that, despite the residents’ screaming against gentrificación, I don’t think it is. It is much worse. La Mítikah – one of the tallest buildings in Latin America together with its ultramodern residential and commercial complexes – has all but smashed the ancient village of Xoco and all its traditions. Residents complain the megaproject has stolen their water. I believe them, but I also know that Mexico City at large is nearing desperation. The world’s largest city, the capital of empires layered on top of one another – and on top of a lake that is all but dried up – is strapped for the most precious of life’s resources. Xoco has come down with a case of development at its worst; La Mítikah is a blueprint of how not to build a city. When I saw the tower, I couldn’t help but remember the glittering steel and glass of Gurgaon (also Gurugaram) in Greater Delhi, where skyscrapers have been raised to form a completely privatized city without a sewage system. A city hidden behind walls and gates. No sidewalks. No public space. No roots. Only roads – deficient for its obscene number of cars – barely connect it to the city it pollutes around it. That is not gentrification; that is a calamity.

As if such rootless development were not enough, Xoco in Mexico City is also squeezed next to a real case of gentrification. At walking distance is the picturesque village of Coyoacán, where the entire world descends upon the famous Casa Azúl, the house of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. It is a place so charming that of course you would want to do more than just stay, you’d want to live there. There is the commons of its central plaza, church, market and tree-lined streets – public space hemmed with all comforts and curiosities to be found in the gentrified travel destinations of the world, places that require some astuteness to enjoy their cultural offerings. As a result, the traditional village that is Coyoacán has become expensive. Placing myself in the shoes of someone who can no longer afford the only world they had ever known, I cannot imagine how they would pinch as I walked around the old streets, watching jetsetters have a good time in the home from which I was excluded, watching them flit in and out to their next fix of “fast food”.

“Mitikah steals our water”/”Death to Gentrification in Xoco”/”My body, my neighborhood…my home…gentrification empties us, it separates us, it dehumanizes us”/”How many more ghosts will I bring in my bag?”

While travel is indeed fortunate, like all blessings, it can turn into dope. I have met many addicts, but one I won’t forget. He seemed too young and too bearded to have been everywhere. Everywhere. In places I had dreamed of visiting, he had already bought and sold a flat out of boredom. He made a point of making me desire some places I had never even heard of. I was envious of him until I wasn’t.

After a six-month stay, the wanderer had been bent on buying an old Italianate villa from the 1800s in Rio de Janeiro. As he sat across from me at a table among mutual friends in one of the city’s lively and alternative botecos, there was something amiss in his sermon as to why his many other cities had been better places. He explained to me everything that was wrong with Rio de Janeiro – oblivious that he had nothing to teach me about my home of more than twenty years. Suspicious was his moaning about what should have still been his honeymoon with the city. Later, he offered details about the imbroglio of buying the old house. It had been his dream to restore such beauty from times past, and it should have been easy considering the property’s derelict state and his exchange rate advantage. He had been disappointed that its price had blown his budget – to say nothing of the cost of refurbishment which would almost double the price. What he had thought would be a cheap country turned out to be nothing of the sort. But it was clear that that wasn’t really what was bothering him.

I decided not to engage him and accept my position at the table, which was unluckier than many of his opinions. One, however, was right, even if unfinished: Rio de Janeiro is difficult to gentrify because of its endemic violence. His friends had rightly advised him that his eccentric taste was located on a street and in neighborhood with limited commerce and transport, a place where he would be exposed to the constant risk of violence – reasons for which generations of their families had long since abandoned such neighborhoods to hide behind gates and doormen near the beach.

The complicated dynamics of history and social disparity have unfortunately left Rio de Janeiro, Brazil’s former capital, ransacked and with an Airbnb crisis that is about five hundred years old. It is a city where people pay for security, carefree living being an asset that not even the city’s wealthiest can guarantee exactly. It is a place where “community” refers to conglomerates of substandard housing, perched ahigh, overlooking some of the most expensive real estate in the Americas. Yet, the city is enchanting, nestled in between beaches, mountains, forests, and plazas. And my interloper was just as bewitched by the city’s beauty as I had been, allured by the magnificence of nature that survives despite all the movement of the city in the exact opposite direction of gentrification while getting even more expensive.

Although Rio de Janeiro is no exception to the two opposing capitalist forces that shape cities – industry and real estate – there is a plot twist in what is called “the Global South”.

Urbanity in the advanced economies of the world had been built by industrialists and the ensuing communities of workers. Under globalization, when manufacturing in those countries relocated to Asia, it left swathes of abandoned neighborhoods for real estate investment and its rentist logic that profits from owning things and not from producing things – or ideas. In Brazil, just like the other commodity producers of the Global South, colonialism and slavery had never permitted much of the industrial development that created such communities of workers – except for small pockets with waves of immigration as in São Paulo, Buenos Aires and Montevideo. Therefore, the grip of real estate in a city like Rio de Janeiro has always been strangling, and in the hands of gentry – making the term gentrification particularly ironic in Latin America.

My unpremeditated lecture on history would have been just as disagreeable at the table as the gentrifier trying to school me about a city he barely knew, so I remained silent as he voiced his frustrations, which I realized weren’t really about the complexity of Rio de Janeiro as much as they were about his inability to find a place to be happy. Before me was a man fortunate enough to have beheld so much beauty in the world, but incapable of sitting still, he only ever saw what was wrong with a place without seeing what was right, which had left him unnourished. It sounded like he would be moving on soon, finding another city that would also remain unfulfilling. He was looking for happiness, but only seemed successful at sustaining shards of it that he mythologized in a monologue about his success as a nomad. I wondered if there was a polite way to interrupt his speech and say that I spotted the bag full of his personal demons sitting next to him on the floor. That he would carry it with him no matter where he went. As Naguib Mahfouz had written: “Home is not where you were born. Home is where all your attempts to escape cease.” Anyway, there was no break in his sermon, so I decided to be generous and give him the attention he wanted – the attention we all want, even when painting graffiti on a wall or writing an essay.

Sitting in that boteco was where I began to realize what philosopher Iris Murdoch meant when saying that love is attention. I would just add that where we get attention is our happy place. I thought about how much it hurts when attention is snatched away from us. It made me think of the dilemma of gentrification through the lens of attention: where we place it; who gets it and what we do with it; how resentful we get when we are no longer the focus; but more importantly, how beauty emerges when we invest stillness long enough to sustain attention, maybe even from generation to generation.

We had our last beer in the boteco, located in the old central region of Rio de Janeiro, away from the beach. It was in one of the city’s rare and tiny pockets of gentrification, not far from the villa that the friend-of-friends had wanted to buy. As I exited, I saw that scaffolding had been raised on the sidewalk across the street. At its height, netting caressed the restoration of a curvaceous façade from the 1800s. Below the scaffolding, homeless people had taken shelter for the night. It was a sight I had seen so many times, but one I had always ignored. I decided it was time to focus my attention, realizing how much I had always averted my eyes, just as pedestrians did when circumnavigating the scaffolding by walking into traffic. In the shadows the planks, there were five people: one woman and four men. They had two dogs on leashes. They had lined their camp with cardboard and old blankets. Clumsily shooing pigeons away from the pipes above, they laughed as they drank the cheapest of liquor that comes in plastic bottles. They saw that I saw that they saw me. But they didn’t know I was remembering the restoration of Notre Dame.

The street got noisier as the sun set. Groups of young people floated like patches of weeds on a river down the street, ebbing and flowing into bars and around potholes. Street vendors hawked their goods, stealing sales from the businesses inside the refurbished old buildings. There was the smell of the sewer, perfume, car exhaust and beer. Red lights flashed from a police car parked on the sidewalk at the corner. The lights created angular shadows as they were projected across the scaffolding. The street contained laughter that roared like the motorbikes that passed us down the street. Fissures in the pavement revealed the cobblestone beneath it.

All cities are improvisations, I thought, as I absorbed the signs of urban creativity, both delightful and repugnant. In that picture I ask myself to conclude whether gentrification is something good or bad. Of course, it should be so simple. Unhinged, the problem with improvisation is it tends toward competition and not cooperation, because the latter requires more planning for a common good. At its worst is the disaster of Gurgaon, which simply dumps sewage into open lots or trucks it to dump in the Yamuna River. Gurgaon was the solution improvised for those with enough money to live and work in Delhi without living and working in Delhi. Gurgaon serves as an example that a city cannot be privatized, enshrining market forces – not citizens.

Conversely, I also conclude that cooperation facilitates public space more than competition, because the focus on community creates a common good. Public space is and has the infrastructure that integrates people in that spider’s web connecting one to all that there is. Cities with public space will always be more desirable than those without it; hence, the warning to residents in neighborhoods in Montevideo and Mexico City not to let gentrification catch them by surprise.

Many battles will be fought between the teams of cooperation and competition, one or the other leaving the field victorious, but hardly winning the war. The war is an internal one to tame all the little dictators demanding attention. That is why I suspect that whomever can answer the question of whether gentrification is progress or problem shall answer all questions, because it inevitably reverts to something happening not only behind the façades of buildings, but behind the faces of individuals trying to reconcile their happiness – their sense of taste and their aversions – with those of a society at large, one that is getting more complex as it gets larger, and ever more covetous of a story, be it in the past or in the future.